笔译(中译英)原文:

笔译中译英一等奖

译文:

点评1:

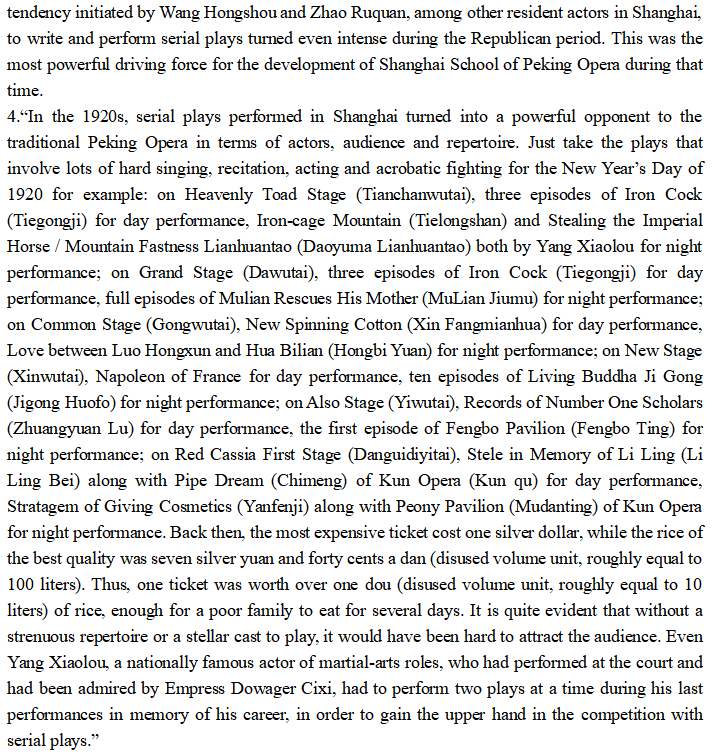

本篇译文准确传达了原文中涉及的主要概念,做到了句子间的衔接连贯,总体上还原了原文的风格。重要概念的准确传达是中华文化外译的基本要求,具备一定的难度,该译者在翻译过程中对归化、异化进行综合运用,尽可能传递原义的同时也保留了一定程度的中华风味。如第一段的“大雅之堂”,译者略去了其本身含有的文化信息,将词性转化为形容词“elegant”,为译语读者消除理解障碍,与句子的结合也相对自然、流畅;第四段的单位概念“担”“斗”,译者则采取了音译形式,同时备注了其内涵意义,显现了中华文化中计量单位的独特之处。这样的翻译方式既能为译语读者所接受,也能提供新鲜感。译者对长句的处理也比较成熟,逻辑比较连贯。如第一段“In terms of singing, ...until they win loud cheers in unison from the audience’”,原文为一个长句,句内结构松散,而译者将其分割成三句,每句句内结构紧凑,主旨表达集中。再如全文最后一句“Even Yang Xiaolou,...in the competition with serial plays.”,通过定语从句、介词短语等理顺原文各短句间的逻辑关系,做到了前后衔接的流畅。

点评2:

就整体而言,该篇译文表义清晰,用词得当,语句通顺,语篇流畅,很好地保留了原文的主题思想和文体风格。就具体细节而言,无论是词语的翻译还是句子的处理,该篇译文都可圈可点。中华文化英译难点之一是对文化词语概念的理解和转换。如原文第一段中的“海派京剧的演出,无论唱念做打,都很卖力气,但往往失之火爆驳杂”,其中“唱念做打”是中国传统戏曲表演中的四种艺术手段,也是戏曲表演的四项基本功,通常被称为“四功”。有道翻译提供的译文是:Sing read do play,谷歌提供的译文是:sing to do,腾讯的译文是:sing, read and fight,Yendex的译文是:the chant done playing等等。在脱离语境的前提下,单单从个体词汇意义孤立地看,以上译文都有不同程度的对应或关联,但在整体上却与原文欲意表达的真实含义相去甚远。译者将其处理为singing, recitation, acting and acrobatic fighting显然比上述译文更加准确清晰,很好地传递了原文的真实意义。此外,衡量译文质量的另外一个重点是译者对冠词、介词、连接词等小词或虚词及其基本句法功能的把握和处理能力,也是衡量译者英语能力的重要依据。在这一方面,本篇译者亦表现突出。这也是该篇译文表义清晰、行文流畅的重要原因。

笔译(英译中)

原文:

The Chinese are comparatively a temperate people. This is owing principally to the universal use of tea, but also to taking their arrack very warm and at their meals, rather than to any notions of sobriety or dislike of spirits. A little of it flushes their faces, mounts into their heads, and induces them when flustered to remain in the house to conceal the suffusion, although they may not be really drunk. This liquor is known as toddy, arrack, saki, tsiu, and other names in Eastern Asia, and is distilled from the yeasty liquor in which boiled rice has fermented under pressure many days. Only one distillation is made for common liquor, but when more strength is wanted, it is distilled two or three times, and it is this strong spirit alone which is rightly called samshu, a word meaning ‘thrice fired.’ Chinese moralists have always inveighed against the use of spirits, and the name of Í-tih, the reputed inventor of the deleterious drink, more than two thousand years before Christ, has been handed down with opprobrium, as he was himself banished by the great Yu for his discovery.

The Shu King contains a discourse by the Lord of Chau on the abuse of spirits. His speech to his brother Fung, B.C. 1120, is the oldest temperance address on record, even earlier than the words of Solomon in the Proverbs. “When your reverendfather, King Wăn, founded our kingdom in the western region, he delivered announcements and cautions to the princes of the various states, their officers, assistants, and managers of affairs, saying, ‘For sacrifices spirits should be employed. …… further, the ruin of the feudal states, small and great, may be traced to this one sin, the free use of spirits.’ King Wăn admonished and instructed the young and those in office managing public affairs, that they should not habitually drink spirits.”

The general and local festivals of the Chinese are numerous, among which the first three days of the year, one or two about the middle of April to worship at the tombs, the two solstices, and the festival of dragon-boats, are common days of relaxation and merry-making, only on the first, however, are the shops shut and business suspended.

The return of the year is an occasion of unbounded festivity and hilarity, as if the whole population threw off the old year with a shout, and clothed themselves in the new with their change of garments. The evidences of the approach of this chief festival appear some weeks previous. The principal streets are lined with tables, upon which articles of dress, furniture, and fancy are disposed for sale in the most attractive manner. Necessity compels many to dispose of certain of their treasures or superfluous things at this season, and sometimes exceedingly curious bits of bric-a-brac, long laid up in families, can be procured at a cheap rate.

A still more praiseworthy custom attending this season is that of settling accounts and paying debts; shopkeepers are kept busy waiting upon their customers, and creditors urge their debtors to arrange these important matters. No debt is allowed to overpass new year without a settlement or satisfactory arrangement, if it can be avoided; and those whose liabilities altogether exceed their means are generally at this season obliged to wind up their concerns and give all their available property into the hands of their creditors.

De Guignes mentions one expedient to oblige a man to pay his debts at this season, which is to carry off the door of his shop or house, for then his premises and person will be exposed to the entrance and anger of all hungry and malicious demons prowling around the streets, and happiness no more revisit his abode; to avoid this he is fain to arrange his accounts. It is a common practice among devout persons to settle with the gods, and on new year’s eve, the temples are unusually thronged by devotees, both male and female, rich and poor. Some persons fast and engage the priests to intercede for them that their sins may be pardoned, while they prostrate themselves before the images amidst the din of gongs, drums, and bells, and thus clear off the old score.

At Canton, some are busy pasting the five slips upon their lintels, signifying their desire that the five blessings which constitute the sum of all human felicity (namely, longevity, riches, health, love of virtue, and a natural death) may be their favored portion. Such sentences as “May the five blessings visit this door,” “May heaven send down happiness,” “May rich customers ever enter this door,” are placed above them; and the doorposts are adorned with others on plain or gold sprinkled red paper, making the entrance quite picturesque. In the hall are suspended scrolls more or less costly, containing antithetical sentences carefully chosen. A literary man would have, for instance, a distich like the following:

May I be so learned as to secrete in my mind three myriads of volumes.

May I know the affairs of the world for six thousand years.

A shopkeeper adorns his door with those relating to trade:

May profits be like the morning sun rising on the clouds.

May wealth increase like the morning tide which brings the rain.

Hold on to benevolence and rectitude in all your trading

The influence of these mottoes, and countless others like them which are constantly seen in the streets, shops, and dwellings throughout the land, is inestimable. Generally it is for good, and as a large proportion are in the form of petition or wish, they show the moral feeling of the people.

笔译英译中一等奖

译文:

1.中国人喝酒比较有节制。这并不是因为持重自好或不喜烈酒,主要是由于饮茶之风盛行,并且餐餐斟酒时,要温酒热饮。小酌几口烈酒,脸上便染上红晕,脑际一片飘然,虽然未醉,屋子里却已溢满酒气。棕榈酒(产自马来西亚),亚力酒(产自东南亚,南亚),清酒(自于日本),中国闽南地区的烧酒,以及东亚地区一些其他名称的酒皆属烈性酒。烈性酒以蒸熟稻米为原料,加入酒曲经数天时间发酵,最后在压力下蒸馏提炼而出。经过一次蒸馏的是低度酒,要想酿出度数更高的酒,需要经过两次或三次蒸馏,这样就能提炼出所谓的“白酒”,或称“三酉”。中国的道德伦理家曾猛烈抨击过饮烈酒现象,早在耶稣诞生两千多年前的(中国古代夏禹时代)仪狄更是成为众矢之的。相传他是我国最早的酿酒人,却因造酒而被大禹驱逐流放。

2.公元前1120年,周公旦为告诫年幼的康叔酗酒的危害,特作《酒诰》,现存于《尚书》中。这是有记载以来中国最早的禁酒令,甚至先于《箴言》(《圣经·旧约》)所罗门之言。《酒诰》中写道:“乃穆考文王,肇国在西土。厥诰毖庶邦、庶士越少正御事朝夕曰:’祀兹酒’......越小大邦用丧,亦罔非酒惟辜。文王诰教小子有正有事:无彝酒。”

3.中国传统节日、地方节日不胜枚举,岁首春节张灯结彩,四月中旬清明祭扫缅怀故人,冬夏两至四序分,端午赛舟群竞渡。节日里人们闲暇自在,尽情欢乐,商铺只在春节三天关门歇业。

4.新年到,万户欢庆千家乐,天地欢腾喜气连,人们辞旧迎新,穿新衣,戴新帽。几周前年味已浓,大街两侧小贩们摆摊售卖,卖衣服、家具陈设,各种精美物件琳琅满目。一些人迫于生计不得不转手家中的值钱玩意,有时会低价卖出家里长期闲置的稀奇精巧的装饰摆件。

5.春节期间另一件值得一提的事情便是清算还债。店主们招揽生意忙得不亦乐乎,债主催促债务人付清欠款。如果不是实在无力还钱,旧账不过年,都该妥善处理,直到双方称心如意为止。到了年关还手头拮据的人为了安心过年,也会倾尽所能,勒紧裤腰带还债。

6.德吉涅斯(法国东方学家、汉学家)提出了一个权宜之计,要想催促欠款,债主可以拆掉欠债人商铺或住处的大门,这样门户大开,欠债人曝露于大街上积压的晦气之中,福气好运定会绕道而行,因此为了避免此种情况发生,他们只好还清账目。春节期间,虔诚之人还有敬香礼佛的习惯,每到除夕,庙宇香火不绝,善男信女纷纷进香祈福,一些人还会斋戒,请求禅师开示,净化身心,忏悔反省。在钟鼓鸣锣声中,在佛像前虔诚跪拜,愿净除业障。

7.在广东,家家忙着贴挥春(即春联,粤语地区称挥春),表达出迎祥纳福的美好愿望(五福分别是:长寿,富贵,康宁,好德,善终)。“五福临门”,“喜从天降”,“贵人进门”都是常见的吉祥话,写在正丹纸或洒金纸上,贴在门柱上,让大门熠熠生辉。大厅里悬挂着价格不等的卷轴,上面有精心挑选的吉利话。例如,文人雅士选对联“揽尽诗书三千卷,阅遍风云六千年”;而经商之人的楹联则写着“利似旭日迎春晖,财如早潮腾紫气。”横批:“昌明德载”。

8.大街小巷,商铺住户,处处张贴春联,上面写有这些寄语或其他大同小异的金玉良言。它们意义重大,绝大多数是祈福祝愿,寓意美好,体现着主人家的品德修养。

点评1:

本参赛译文行文流畅,语言凝练,整饬有序且富有文采。由于原文本身是对中国传统文化的介绍,因而在英译汉的过程中采用归化的翻译方法是合乎情理的,这这主要体现在该译文的选词和句式的调配、变通中。

首先,在选词上译者有着高度的敏锐力把控力,如第六段中“开示”“业障”等佛教用语的选用,符合语境并传达了原义;第七段“正丹纸”“洒金纸”以及几幅对联的翻译也符合汉语语言习惯,同时展现了译者良好的人文功底及知识储备。

另外,译者通过对句子的变通,使译文富有感染力,还原原文文体风格。如第三段“岁首春节张灯结彩,四月中旬清明祭扫缅怀故人,冬夏两至四序分,端午赛舟群竞渡。”一句,译者通过适当的增译使句式整饬、富有节奏感,符合汉语文化的审美。

点评2:

衡量译本优劣有两条最基本的标准:其一、对原文的理解和忠实;其二、在译入语中将原文意义的准确和流畅表达。该译文的优点恰恰是很好地满足了这两条标准。首先,对原文的正确理解表现了译者扎实的原语语言功底,其中包括理性的词汇概念意义、潜在的文化背景意义、纷繁的多重语义关系、复杂的句法结构的把握;其次,而做到了译文准确流畅则表现了译者对译入语语言资源和文化知识的熟悉程度。译文中使用的“敬香礼佛”、“香火不绝”、“善男信女”、“进香祈福”、“禅师开示”、“净化身心”、“忏悔反省”、“虔诚跪拜”、“净除业障”、“五福临门”、“喜从天降”、“贵人进门”等等文化词语的选用既真实而恰当地尊重了汉语四字格的表达习惯,又还原了原语中所包含的文化信息,符合汉语读者对译文的语言文化心理期待。在翻译方法的选择上,译者不拘一格,能够灵活运用直译和意译的翻译手段,直译不失其达,意译不失其真,切实做到了直译尽其所能,意译按其所需。